Monarchism In Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of

Japan: The Japanese Emperor is the last remaining head of state with the title of "Emperor". The Imperial House of Japan is the world's oldest, having existed continuously since at least the 6th century. Since the adoption of the 1947 Japanese constitution, the Emperor has been made a ceremonial head of state, without any nominal political powers. Today,

Japan: The Japanese Emperor is the last remaining head of state with the title of "Emperor". The Imperial House of Japan is the world's oldest, having existed continuously since at least the 6th century. Since the adoption of the 1947 Japanese constitution, the Emperor has been made a ceremonial head of state, without any nominal political powers. Today,

France: During the

France: During the  United Kingdom: In England, royalty ceded power to other groups in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced

United Kingdom: In England, royalty ceded power to other groups in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced

Honduras: After the independence of the general captaincy of Guatemala from the

Honduras: After the independence of the general captaincy of Guatemala from the  Mexico: After obtaining independence from Spain, the

Mexico: After obtaining independence from Spain, the

The Monarchist League

IMC

official site of the :fr:Conférence Monarchiste Internationale, International Monarchist Conference.

SYLM

Support Your Local Monarch, the independent monarchist community. {{Monarchies Monarchism, ja:君主主義

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

. Conversely, the opposition to monarchical rule is referred to as republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

.

Depending on the country, a royalist may advocate for the rule of the person who sits on the throne, a regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, a pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term is often used to suggest that a claim is not legitimate.Curley Jr., Walter J. P. ''Monarchs-in-Waiting'' ...

, or someone who would otherwise occupy the throne but has been deposed.

History

Monarchical rule is among the oldest political institutions. The similar form of societal hierarchy known aschiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

or tribal kingship

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categorized as ...

is prehistoric. Chiefdoms provided the concept of state formation, which started with civilizations such as Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, Ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

. In some parts of the world, chiefdoms became monarchies.

Monarchs have generally ceded power in the modern era, having substantially diminished since World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. This process can be traced back to the 18th century, when Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

and others encouraged "enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism (also called enlightened despotism) refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhance ...

", which was embraced by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 unt ...

and by Catherine II of Russia

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

.

In 1685

Events

January–March

* January 6 – American-born British citizen Elihu Yale, for whom Yale University in the U.S. is named, completes his term as the first leader of the Madras Presidency in India, administering the colony ...

the Enlightenment began. This would result in new anti-monarchist ideas which resulted in several revolutions such as the 18th century American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

and the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

which were both additional steps in the weakening of power of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an monarchies. Each in its different way exemplified the concept of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

upheld by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

. 1848 then ushered in a wave of revolutions against the continental European monarchies. World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and its aftermath saw the end of three major European monarchies: the Russian Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to th ...

dynasty, the German Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

dynasty, including all other German monarchies and the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

dynasty.

With the arrival of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

by the end of 1947, the remaining Eastern European monarchies, namely the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

, the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, the Kingdom of Albania Kingdom of Albania may refer to:

*Kingdom of Albania (medieval) — from the Capetian House of Anjou

*Albanian Kingdom (1928–1939) — from the House of Zogu

*Albanian Kingdom (1939–1943) — from the House of Savoy during the Italian occupati ...

, the Kingdom of Bulgaria

The Tsardom of Bulgaria ( bg, Царство България, translit=Tsarstvo Balgariya), also referred to as the Third Bulgarian Tsardom ( bg, Трето Българско Царство, translit=Treto Balgarsko Tsarstvo, links=no), someti ...

and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

, were all abolished and replaced by socialist republics

Several past and present states have declared themselves socialist states or in the process of building socialism. The majority of self-declared socialist countries have been Marxist–Leninist or inspired by it, following the model of the Sovi ...

.

Africa

Central Africa: In 1966, theCentral African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

was overthrown at the hands of Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa (; 22 February 1921 – 3 November 1996), also known as Bokassa I, was a Central African political and military leader who served as the second president of the Central African Republic (CAR) and as the emperor of its s ...

during the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état

The Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état was a coup d'état staged by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, commander-in-chief of the Central African Republic (CAR) army, and his officers against the government of President David Dacko on 31 December 1965 and 1 Januar ...

. He established the Central African Empire

From 4 December 1976 to 21 September 1979, the Central African Republic was officially known as the Central African Empire (french: Empire centrafricain), after military dictator (and president at the time) Marshal Jean-Bédel Bokassa declared ...

in 1976 and ruled as Emperor Bokassa I until 1979, when he was subsequently deposed during Operation Caban

Operation Caban was a bloodless military operation by France in September 1979 to depose Emperor Bokassa I, reinstate the exiled former president David Dacko, and rename the Central African Empire back to Central African Republic.

History

By J ...

and Central Africa returned to republican rule.

Ethiopia: In 1974, one of the world's oldest monarchies was abolished in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

with the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

.

Asia

China:China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

possessed a monarchy from prehistoric times up until 1912, when Emperor Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

was deposed. He was briefly restored to the throne for twelve days during the Manchu Restoration

The Manchu Restoration or Dingsi Restoration (), also known as Zhang Xun Restoration (), or Xuantong Restoration (), was an attempt to restore the Chinese monarchy by General Zhang Xun, whose army seized Beijing and briefly reinstalled the las ...

in 1917, but this attempt was quickly undone by republican forces. The end of the Chinese monarchy ushered in the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

.

India: In India, monarchies recorded history of thousands of years before the country was declared a republic country in 1950. King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

had previously been the last Emperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 22 ...

until August 1947, when the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

dissolved. Karan Singh

Karan Singh (born 9 March 1931) is an Indian politician and philosopher. He is the son of the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, Sir Hari Singh. He was the prince regent of Jammu and Kashmir until 1952. From 19 ...

served as the last prince regent of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

until November 1952.

Iran: Monarchism possessed an important role in the 1979 Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

and also played a role in the modern political affairs of Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

. Nepal was one of the last states to have had an absolute monarch, which continued until King Gyanendra

Gyanendra Shah ( ne, ज्ञानेन्द्र शाह, born 7 July 1947) is a former monarch who was the last King of Nepal, reigning from 2001 to 2008. As a child, he was briefly king from 1950 to 1951, when his grandfather, Tribhuva ...

was peacefully deposed in May 2008 and the country became a federal republic.

Japan: The Japanese Emperor is the last remaining head of state with the title of "Emperor". The Imperial House of Japan is the world's oldest, having existed continuously since at least the 6th century. Since the adoption of the 1947 Japanese constitution, the Emperor has been made a ceremonial head of state, without any nominal political powers. Today,

Japan: The Japanese Emperor is the last remaining head of state with the title of "Emperor". The Imperial House of Japan is the world's oldest, having existed continuously since at least the 6th century. Since the adoption of the 1947 Japanese constitution, the Emperor has been made a ceremonial head of state, without any nominal political powers. Today, Naruhito

is the current Emperor of Japan. He acceded to the Chrysanthemum Throne on 1 May 2019, beginning the Reiwa era, following the abdication of his father, Akihito. He is the 126th monarch according to Japan's traditional order of succession.

...

serves as the Emperor of Japan and enjoys wide support from the Japanese population.

Europe

Albania: The last separate monarchy to take root in Europe,Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

began its recognised modern existence as a principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) can either be a monarchical feudatory or a sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a regnant-monarch with the title of prince and/or princess, or by a monarch with another title considered to fall under ...

(1914) and became a kingdom after a republican interlude in 1925–1928. Since 1945 the country has operated as an independent republic. The Albanian Democratic Monarchist Movement Party

Albanian Democratic Monarchist Movement Party ( sq, Partia Lëvizja Monarkiste Demokrate Shqiptare) is a political party in Albania led by Guri Durollari. The party contested the 2005 parliamentary elections, and got around 0.1% of the votes.

See ...

(founded in 2004) and the Legality Movement Party

The Legality Movement Party (; PLL) is a right-wing monarchist political party in Albania. It supports the return to power of the House of Zogu under Crown Prince Leka of the Albanians. In the 2001 parliamentary election it was part of the Unio ...

(founded in 1924) advocate restoration of the House of Zogu

The House of Zogu, or Zogolli during Ottoman times and until 1922, is an Albanian dynasty whose roots date back to the early 20th century. The family provided the first president and the short-lived modern Albanian Kingdom with its only monarch, ...

as monarchs—the concept has gained little electoral support.

Austria-Hungary: Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary, the Republic of German-Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wi ...

was proclaimed. The Constitutional Assembly of German Austria passed the Habsburg Law

The Habsburg Law (''Habsburgergesetz'' (in full, the Law concerning the Expulsion and the Takeover of the Assets of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine) ''Gesetz vom 3. April 1919 betreffend die Landesverweisung und die Übernahme des Vermögens des H ...

, which permanently exiled the Habsburg family from Austria. Despite this, significant support for the Habsburg family persisted in Austria. Following the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

of 1938, the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

government suppressed monarchist activities. By the time Nazi rule ended in Austria, support for monarchism had largely evaporated.

In Hungary, the rise of the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

in 1919 provoked an increase in support for monarchism; however, efforts by Hungarian monarchists failed to bring back a royal head of state, and the monarchists settled for a regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, Admiral Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya ( hu, Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós; ; English: Nicholas Horthy; german: Nikolaus Horthy Ritter von Nagybánya; 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957), was a Hungarian admiral and dictator who served as the Regent o ...

, to represent the monarchy until it could be restored. Horthy ruled as regent from 1920 to 1944. During his regency, attempts were made by Karl von Habsburg

Karl von Habsburg (given names: ''Karl Thomas Robert Maria Franziskus Georg Bahnam''; born 11 January 1961) is an Austrian politician and the head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, therefore being a claimant to the defunct Austro-Hungarian t ...

() to return to the Hungarian throne, which ultimately failed. Following Karl's death in 1922, his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary was inherited by Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (german: Franz Joseph Otto Robert Maria Anton Karl Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Ludwig Gaetan Pius Ignatius, hu, Ferenc József Ottó Róbert Mária Antal Károly Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Lajos Gaetan ...

(1912–2011), although no further attempts were made to take the Hungarian throne.

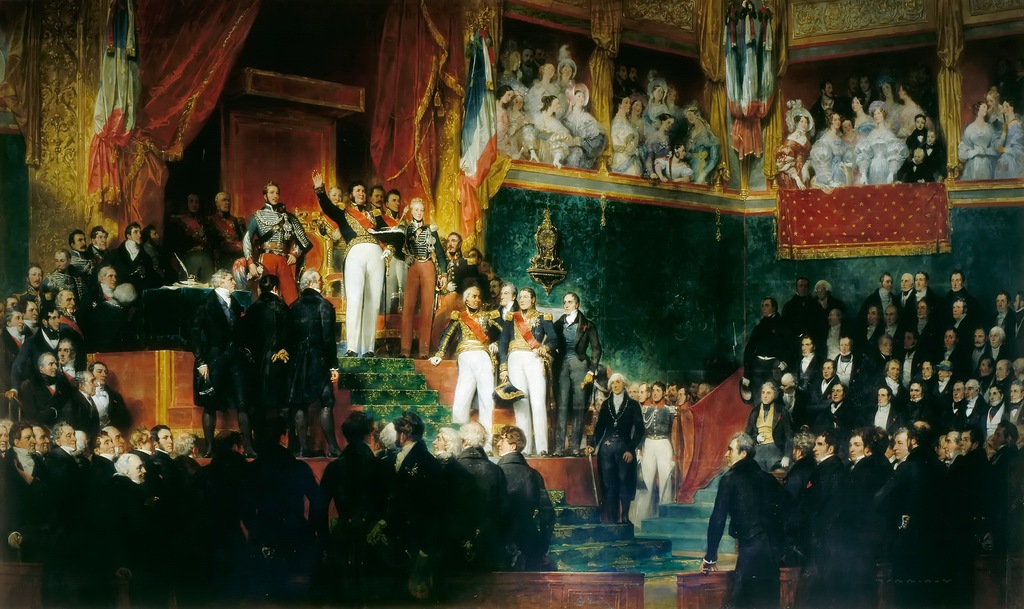

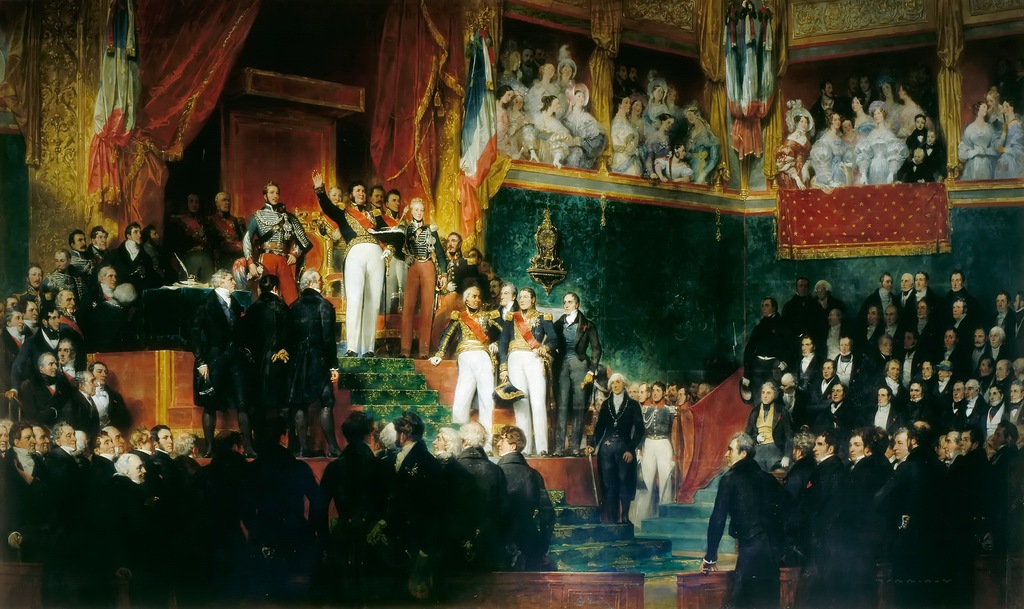

France: During the

France: During the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

was proclaimed in 1792 following the overthrow of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

. The Republic failed, and transitioned into the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

under Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1804. Napoleon's fall in 1814 led to the Bourbon Restoration in France

The Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history during which the House of Bourbon returned to power after the first fall of Napoleon on 3 May 1814. Briefly interrupted by the Hundred Days War in 1815, the Restoration lasted until the J ...

under Louis XVIII. The restored Kingdom of France lasted until 1830, save a brief period during the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

(1815) when Napoleon attempted to retake control. In 1830, King Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Loui ...

was overthrown during the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

and replaced with his cousin, Louis Philippe I

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary War ...

, who reigned as "King of the French

The precise style of French sovereigns varied over the years. Currently, there is no French sovereign; three distinct traditions (the Legitimist, the Orleanist, and the Bonapartist) exist, each claiming different forms of title.

The three styles ...

". Louis Phillipe I ruled for 18 years, until his abdication due to the French Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (french: Révolution française de 1848), also known as the February Revolution (), was a brief period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundation ...

. After this, the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic (french: Deuxième République Française or ), officially the French Republic (), was the republican government of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in February 1848, with the February Revo ...

was formed, which lasted for just four years. Its first president, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, initiated a coup in 1851 and proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

the following year, establishing the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Empire, Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the French Second Republic, Second and the French Third Republic ...

. It lasted until 1870, and was succeeded by the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

.

Following Napoleon III's fall in 1870, Henri, Count of Chambord

Henri, Count of Chambord and Duke of Bordeaux (french: Henri Charles Ferdinand Marie Dieudonné d'Artois, duc de Bordeaux, comte de Chambord; 29 September 1820 – 24 August 1883) was disputedly King of France from 2 to 9 August 1830 as Hen ...

was offered the French throne, but he declined due to a disagreement with the French government. Due to his refusal, the French royalists intended to offer the crown to the Orleanist Prince Philippe, Count of Paris

Prince Philippe of Orléans, Count of Paris (Louis Philippe Albert; 24 August 1838 – 8 September 1894), was disputedly King of the French from 24 to 26 February 1848 as Louis Philippe II, although he was never officially proclaimed as such. ...

upon Henri's death. However, Henri lived longer than expected, and by the time of his death in 1883, support for monarchy had weakened too greatly to offer Phillipe the crown.

Since then, figures and groups such as Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet, and critic. He was an organizer and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that is monarchist, anti-parl ...

(1868–1952) and Action Française

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 f ...

(founded in 1899) have advocated for the restoration of the monarchy. During World War II, many French monarchists fought (1940–1944) with the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

. Some, such as Henri d'Astier de la Vigerie Henri d'Astier de La Vigerie (11 September 1897 – 10 October 1952) was a French soldier, ''Résistance'' member, and conservative politician.

Life

Henri d'Astier was born in Villedieu-sur-Indre, a small village in the Indre département of cent ...

pushed for a coup against Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, which would restore Henri, Count of Paris to the throne of France as King. However, this idea was stopped by Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, among others. After the war, Henri enjoyed wide popularity and maintained a friendship with Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, whom he tried to convince to support a restoration of the monarchy. While de Gaulle was sympathetic, he ultimately abandoned the idea, and no serious attempt to restore the monarchy ever came to fruition. Today, the majority of French monarchists, a minority in France, are Orléanist

Orléanist (french: Orléaniste) was a 19th-century French political label originally used by those who supported a constitutional monarchy expressed by the House of Orléans. Due to the radical political changes that occurred during that centu ...

s and advocate for a restoration of the crown under Jean, Count of Paris

Jean Carl Pierre Marie d'Orléans (born 19 May 1965) is the current head of the House of Orléans. Jean is the senior male descendant by primogeniture in the male-line of Louis-Philippe I, King of the French, and thus, according to the Orléan ...

, pretender to the throne as ''Jean IV''. A smaller monarchist group, known as Legitimists

The Legitimists (french: Légitimistes) are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They re ...

, instead support Louis Alphonse de Bourbon

Louis Alphonse de BourbonHis name is given as "Prince Louis Alphonse of Bourbon and Martínez-Bordiú, Duke of Anjou" by Olga S. Opfell in ''Royalty who Wait: The 21 Heads of Formerly Regnant Houses of Europe'' (2001), p. 11. ( es, Luis Alfonso ...

, styled ''Louis XX''.

Germany: In 1920s Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

a number of monarchists gathered around the German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

(founded in 1918), which demanded the return of the Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

monarchy and an end to the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

; the party retained a large base of support until the rise of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

in the 1930s, as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

staunchly opposed monarchism.

Italy: The aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

saw the return of monarchist/republican rivalry in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, where a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

was held on whether the state should remain a monarchy or become a republic. The republican side won the vote by a narrow margin, and the modern Republic of Italy was created.

Liechtenstein: There have been 16 monarchs of the Principality of Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constitutional monarch ...

since 1608. The current Prince of Liechtenstein, Hans-Adam II

Hans-Adam II (Johannes Adam Ferdinand Alois Josef Maria Marco d'Aviano Pius; born 14 February 1945) is the reigning Prince of Liechtenstein, since 1989. He is the son of Prince Franz Joseph II and his wife, Countess Georgina von Wilczek. He al ...

, has reigned since 1989. In 2003, during a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, 64.3% of the population voted to increase the power of the prince.

Norway: The position of King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingdoms ...

has existed continuously since the unification of Norway

The Unification of Norway (Norwegian Bokmål: ''Rikssamlingen'') is the process by which Norway merged from several petty kingdoms into a single kingdom, predecessor to modern Kingdom of Norway.

History

King Harald Fairhair is the monarch who ...

in 872. Following the dissolution of union with Sweden and the abdication of King Oscar II

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Queen Josephine. He inherited the Swedish and Norweg ...

of Sweden as King of Norway, the 1905 Norwegian monarchy referendum

A referendum on retaining the monarchy or becoming a republic was held in Norway on 12 and 13 November 1905. Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1437 Voters were asked whether they approved of the S ...

saw 78.94% of Norway's voters approving the government's proposition to invite Prince Carl of Denmark to become their new king. Following the vote, the prince then accepted the offer, becoming King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VI ...

.

In 2022, the Norwegian parliament held a vote on abolishing the monarchy and replacing it with a republic. The proposal failed, with a 134–35 result in favor of retaining the monarchy. The idea was highly controversial in Norway, as the vote was spearheaded by the sitting Minister of Culture and Equality

The Minister of Culture and Equality ( no, Kultur- og likestillingsminister; sometimes just ''kulturminister'' or ''likestillingsminister'' depending on context) is a councilor of state and chief of the Norway's Ministry of Culture. The ministr ...

, who had sworn an oath of loyalty to King Harald V of Norway

Harald V ( no, Harald den femte, ; born 21 February 1937) is King of Norway. He acceded to the throne on 17 January 1991.

Harald was the third child and only son of King Olav V of Norway and Princess Märtha of Sweden. He was second in the lin ...

the previous year. Additionally, when polls were conducted, it was found that 84% of the Norwegian public supported the monarchy, with only 16% unsure or against the monarchy.

Russia: Monarchy in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

collapsed in March 1917, following the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

of Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

. Parts of the White movement, and in particular émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

s and their (founded in 1921 and now based in Canada) continued to advocate for monarchy as "the sole path to the rebirth of Russia". In the modern era, a minority of Russians, including Vladimir Zhirinovsky

Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky, ''né'' Eidelshtein (russian: link=false, Эйдельштейн) (25 April 1946 – 6 April 2022) was a Russian right-wing populist politician and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) f ...

(1946–2022), have openly advocated for a restoration of the Russian monarchy

A restoration of the Russian monarchy is a hypothetical event in which the Russian monarchy, which has been non-existent since the abdication of the reigning Nicholas II on 15 March 1917 and the murder of him and the rest of his closest family i ...

. Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna is widely considered the valid heir to the throne, in the event that a restoration occurs. Other pretenders and their supporters dispute her claim.

Spain: In 1868, Queen Isabella II of Spain

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successio ...

was deposed during the Spanish Glorious Revolution. The Duke of Aosta

Duke of Aosta ( it, Duca d'Aosta; french: Duc d'Aoste) was a title in the Italian nobility. It was established in the 13th century when Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, made the County of Aosta a duchy. The region was part of the Savoyard stat ...

, an Italian prince, was invited to rule and replace Isabella. He did so for a three-year period, reigning as Amadeo I before abdicating in 1873, resulting in the establishment of the First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic ( es, República Española), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic, was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after th ...

. The republic lasted less than two years, and was overthrown during a coup by General Arsenio Martínez Campos

Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, born Martínez y Campos (14 December 1831, in Segovia, Spain – 23 September 1900, in Zarauz, Spain), was a Spanish officer who rose against the First Spanish Republic in a military revolution in 1874 and res ...

. Campos restored the Bourbon monarchy

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, memb ...

under Isabella II's more popular son, Alfonso XII

Alfonso XII (Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María de la Concepción Gregorio Pelayo; 28 November 185725 November 1885), also known as El Pacificador or the Peacemaker, was King of Spain from 29 December 1874 to his death in 188 ...

.

After the 1931 Spanish local elections

The 1931 Spanish local elections were held on 12 April throughout all Spain municipalities to elect 80,472 councillors.

These elections were perceived as a plebiscite on the monarchy of Alfonso XIII. The Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed after ...

, King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alfo ...

voluntarily left Spain and republicans proclaimed a Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

.

After the assassination of opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician, minister of Finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Second Republic. During t ...

in 1936, right-wing forces banded together to overthrow the Republic. During the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

of 1936 to 1939, General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

established the basis for the Spanish State

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spani ...

(1939–1975). In 1938, the autocratic government of Franco claimed to have reconstituted the Spanish monarchy ''in absentia'' (and in this case ultimately yielded to a restoration, in the person of King Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos I (;,

* ca, Joan Carles I,

* gl, Xoán Carlos I, Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 Novem ...

).

In 1975, Juan Carlos I

Juan Carlos I (;,

* ca, Joan Carles I,

* gl, Xoán Carlos I, Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 Novem ...

became King of Spain and began the Spanish transition to democracy

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

. He abdicated in 2014, and was succeeded by his son Felipe VI

Felipe VI (;,

* eu, Felipe VI.a,

* ca, Felip VI,

* gl, Filipe VI, . Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. He is the son of former King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía, and h ...

.

United Kingdom: In England, royalty ceded power to other groups in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced

United Kingdom: In England, royalty ceded power to other groups in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

to sign the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

, which guaranteed the English barons certain liberties and established that the king's powers were not absolute. King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was executed in 1649, and the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

was established as a republic. Highly unpopular, the republic was ended in 1660, and the monarchy was restored under King Charles II. In 1687–88, the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

and the overthrow of King James II James II may refer to:

* James II of Avesnes (died c. 1205), knight of the Fourth Crusade

* James II of Majorca (died 1311), Lord of Montpellier

* James II of Aragon (1267–1327), King of Sicily

* James II, Count of La Marche (1370–1438), King C ...

established the principles of constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, which would later be worked out by Locke and other thinkers. However, absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

, justified by Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

in ''Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to some ...

'' (1651), remained a prominent principle elsewhere.

Following the Glorious Revolution, William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

were established as constitutional monarchs, with less power than their predecessor James II. Since then, royal power has become more ceremonial, with powers such as refusal to assent last exercised in 1708 by Queen Anne. Once part of the United Kingdom (1801–1922), southern Ireland rejected monarchy and became the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

in 1949. Support for a ceremonial monarchy remains high in Britain: Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

(), possessed wide support from the U.K.'s population.

Vatican City State: The Vatican City State is considered to be Europe's last absolute monarchy. The micronation is headed by the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, who doubles as its monarch according to the Vatican constitution. The nation was formed under Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

in 1929, following the signing of the Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty ( it, Patti Lateranensi; la, Pacta Lateranensia) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle ...

. It was the successor state to the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, which collapsed under Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

in 1870. Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013. ...

(in office from 2013) serves as the nation's absolute monarch.

North America

Canada: Canada possesses one of the world's oldest continuous monarchies, having been established in the 16th century. QueenElizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

had served as its sovereign since her ascension to the throne in 1952 until her death in 2022.

Costa Rica: The struggle between monarchists and republicans led the country to confront each other in the Costa Rican civil war of 1823. Political figures who stand out as Costa Rican monarchists include Joaquín de Oreamuno y Muñoz de la Trinidad, José Santos Lombardo y Alvarado and José Rafael Gallegos Alvarado. among others .Costa Rica stands out for being one of the few countries with a foreign monarchism, that is, where the monarchists did not intend to establish an indigenous monarchy. Costa Rican monarchists were loyal to Emperor Agustín de Iturbide of the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

.

Spanish empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, she joined the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

for a brief period, this unleashed the division of the Honduran elites. These were divided between the annexationists, made up mostly of illustrious spaniskh-descendant families and members of the conservative party who supported the idea of being part of an empire, and the liberals who wanted Central America to be a separate nation under a republican system.

The greatest example of this separation was in the two most important cities of the province, on the one hand Comayagua

Comayagua () is a city, municipality and old capital of Honduras, located northwest of Tegucigalpa on the highway to San Pedro Sula and above sea level.

The accelerated growth experienced by the city of Comayagua led the municipal authoriti ...

, which firmly supported the legitimacy of Iturbide I as emperor and remained a pro-monarchist bastion in Honduras, and on the other hand Tegucigalpa

Tegucigalpa (, , ), formally Tegucigalpa, Municipality of the Central District ( es, Tegucigalpa, Municipio del Distrito Central or ''Tegucigalpa, M.D.C.''), and colloquially referred to as ''Tegus'' or ''Teguz'', is the capital and largest city ...

who supported the idea of forming a federation of Central American states under a republican system.

Mexico: After obtaining independence from Spain, the

Mexico: After obtaining independence from Spain, the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

was established under Emperor Agustín I

Agustín is a Spanish given name and sometimes a surname. It is related to Augustín. People with the name include:

Given name

* Agustín (footballer), Spanish footballer

* Agustín Calleri (born 1976), Argentine tennis player

* Agustín Cár ...

. His reign lasted less than one year, and he was forcefully deposed. In 1864, the Second Mexican Empire

The Second Mexican Empire (), officially the Mexican Empire (), was a constitutional monarchy established in Mexico by Mexican monarchists in conjunction with the Second French Empire. The period is sometimes referred to as the Second French i ...

was formed under Emperor Maximilian I Maximilian I may refer to:

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, reigned 1486/93–1519

*Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, reigned 1597–1651

*Maximilian I, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1636-1689)

*Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria, reigned 1795� ...

. Maximilian's government enjoyed French aid, but opposition from America, and collapsed after three years. Much like Agustín I, Maximilian I was deposed and later executed by his republican enemies. Since 1867, Mexico has not possessed a monarchy.

Today, some Mexican monarchist organizations advocate for Maximilian von Götzen-Iturbide or Carlos Felipe de Habsburgo

Carlos Felipe María Otón Lucas Marcos de Aviano Melchor de Habsburgo-Lorena y Arenberg (born 18 October 1954) or simply known as Archduke Carlos Felipe, is a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. He is the first male of the former ruling ho ...

to be instated as the Emperor of Mexico.

Nicaragua: The miskito Miskito may refer to:

* Miskito people, ethnic group in Honduras and Nicaragua

** Miskito Sambu, branch of Miskito people with African admixture

** Tawira Miskito, branch of Miskito people of largely indigenous origin

* Miskito language, original la ...

ethnic group inhabits part of the Atlantic coast of Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

, by the beginning of the 17th century the said ethnic group was reorganized under a single chief known as Ta Uplika, for the reign of his grandson King Oldman I this group had a very close relationship With the English, they managed to turn the Mosquitia coast into an English protectorate that would decline in the 19th century until it completely disappeared in 1894 with the abdication of Robert II.

Currently, the Miskitos who are shot between the two countries have denounced the neglect of their communities and abuses committed by the authorities. As a result of this, in Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

several Miskito people began a movement of separatism from present-day Nicaragua and a re-institution of the monarchy.

United States: English settlers first established the colony of Jamestown in 1607, taking its name after King James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

. For 169 years, the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

were ruled by the authority of the British crown. The Thirteen American Colonies possessed a total of 10 monarchs, ending with George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, the colonies declared independence from Britain in 1776. Despite erroneous popular belief, the Revolutionary war was in fact fought over independence, not anti-monarchism as is commonly believed. In fact, many American colonists who fought in the war against George III were monarchists themselves, who opposed George, but desired to possess a different king. Additionally, the American colonists received the financial support of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

and Charles III of Spain

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_d ...

during the war.

After the U.S. declared its independence, the form of government by which it would operate still remained unsettled. At least two of America's Founding Fathers

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

, Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham (May 27, 1738 – June 11, 1796; sometimes spelled ''Nathanial'') was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Massachusetts. He was a delegate from the Bay Colony to the Continental Congress and for six months ...

, believed that America should be an independent monarchy, . Various proposals to create an American monarchy were considered, including the Prussian scheme The Prussian scheme is the name of a reported 1786 attempt by President of the Continental Congress Nathaniel Gorham, acting in possible concert with other persons influential in the government of the United States, to establish a monarchy in the U ...

which would have made Prince Henry of Prussia king of the United States. Hamilton proposed that the leader of America should be an elected monarch, while Gorham pushed for a hereditary monarchy. U.S. military officer Lewis Nicola

Lewis Nicola (1717 – August 9, 1807) was an Irish-born American military officer, merchant, and writer who held various military and civilian positions throughout his career. Nicola is most notable for authoring the Newburgh letter, which u ...

also desired for America to be a monarchy, suggesting George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

accept the crown of America, which he declined. All attempts ultimately failed, and America was founded a Republic.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, a return to monarchy was considered as a way to solve the crisis, though it never came to fruition. Since then, the idea has possessed low support, but has been advocated by some public figures such as Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram (December 16, 1863 – September 22, 1942) was a prolific and influential American architect of collegiate and ecclesiastical buildings, often in the Gothic Revival style. Cram & Ferguson and Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson are partner ...

, Solange Hertz

Nellie Solange Strong Hertz (née Strong; January 1, 1920 – October 3, 2015) was an American traditionalist Catholic author, who published almost two dozen books on Catholicism, and wrote for notable magazines including The Remnant (newspaper) ...

, Leland B. Yeager

Leland Bennett Yeager (; October 4, 1924 – April 23, 2018) was an American economist dealing with monetary policy and international trade.

Biography

Yeager graduated from Oberlin College in 1948 with an A.B. and was granted an M.A. from Columb ...

, Michael Auslin

Michael Robert Auslin (born 17 March 1967) is an American writer, policy analyst, historian, and scholar of Asia. He is currently the Payson J. Treat Distinguished Research Fellow in Contemporary Asia at the Hoover Institution, Stanford Univers ...

, Charles A. Coulombe

Roy-Charles A. Coulombe (born November 8, 1960), known as Charles Coulombe, is an American Catholic author, historian, and lecturer. Coulombe is known for his advocacy of monarchism.

Early life and education

Coulombe was born in Manhattan on ...

, and Curtis Yarvin

Curtis Guy Yarvin (born 1973), also known by the pen name Mencius Moldbug, is an American blogger, software engineer, and Internet entrepreneur. He is known, along with fellow theorist Nick Land, for founding the anti-egalitarian and anti-demo ...

.

Current monarchies

The majority of current monarchies areconstitutional monarchies

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. In most of these, the monarch wields only symbolic power, although in some, the monarch does play a role in political affairs. In Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, for instance, King Bhumibol Adulyadej

Bhumibol Adulyadej ( th, ภูมิพลอดุลยเดช; ; ; (Sanskrit: ''bhūmi·bala atulya·teja'' - "might of the land, unparalleled brilliance"); 5 December 192713 October 2016), conferred with the title King Bhumibol the Great ...

, who reigned from 1946 to 2016, played a critical role in the nation's political agenda and in various military coups. Similarly, in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, King Mohammed VI Muhammad VI may refer to:

* Muhammad Imaaduddeen VI (1868–1932), sultan of the Maldives from 1893 to 1902

* Mehmed VI (1861–1926), sultan of Ottoman Empire, from 1918 to 1922

* Mohammed VI of Morocco

Mohammed VI ( ar, محمد السادس ...

wields significant, but not absolute power.

Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constitutional monarchy ...

is a democratic principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) can either be a monarchical feudatory or a sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a regnant-monarch with the title of prince and/or princess, or by a monarch with another title considered to fall under ...

whose citizens have voluntarily given more power to their monarch in recent years.

There remain a handful of countries in which the monarch is the true ruler. The majority of these countries are oil-producing Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

Islamic monarchies

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main ...

like Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, Qatar

Qatar (, ; ar, قطر, Qaṭar ; local vernacular pronunciation: ), officially the State of Qatar,) is a country in Western Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it sh ...

, Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

, and the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia (The Middle East). It is located at th ...

. Other strong monarchies include Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely sur ...

and Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its no ...

.

Political philosophy

Absolute monarchy stands as an opposition toanarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

and, additionally since the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

; liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

, communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

.

Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (german: Franz Joseph Otto Robert Maria Anton Karl Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Ludwig Gaetan Pius Ignatius, hu, Ferenc József Ottó Róbert Mária Antal Károly Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Lajos Gaetan ...

advocated a form of constitutional monarchy based on the primacy of the supreme judicial function, with hereditary succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.mediation

Mediation is a structured, interactive process where an impartial third party neutral assists disputing parties in resolving conflict through the use of specialized communication and negotiation techniques. All participants in mediation are ...

by a tribunal

A tribunal, generally, is any person or institution with authority to judge, adjudicate on, or determine claims or disputes—whether or not it is called a tribunal in its title.

For example, an advocate who appears before a court with a single ...

is warranted if suitability is problematic.

Non-partisanship

British political scientistVernon Bogdanor

Vernon Bernard Bogdanor (; born 16 July 1943) is a British political scientist and historian, research professor at the Institute for Contemporary British History at King's College London and professor of politics at the New College of the Hu ...

justifies monarchy on the grounds that it provides for a nonpartisan head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

, separate from the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

, and thus ensures that the highest representative of the country, at home and internationally, does not represent a particular political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

, but all people. Bogdanor also notes that monarchies can play a helpful unifying role in a multinational state